Immediate

August 15, 2019 @ 7:30 PM

Greenlight Books with Amy Hempel

Brooklyn, NY

August 19, 2019 @ 7:00 PM

Politics and Prose

Washington, DC

August 20, 2019 @ 7:00 PM

McNally Jackson with Darcey Steinke

New York, NY

August 26, 2019 @ 7:30 PM

Green Apple Books

San Francisco, CA

August 27, 2019 @ 7:30 PM

Powell’s City of Books

Portland, OR

August 28, 2019 @ 7:00 PM

Elliott Bay Books

Seattle, WA

September 6, 2019 @ 7:00 PM

Twenty Stories

Providence, RI

September 24, 2019 @ 7:00 PM

Newtonville Books

Newton, MA

The Long Accomplishment

The Long Accomplishment (August, 2019, Hardcover)

Rick Moody, the award-winning author of The Ice Storm, shares the harrowing true story of the first year of his second marriage—an eventful month-by-month account—in The Long Accomplishment: A Memoir of Struggle and Hope in Matrimony

At this story’s start, Moody, a recovering alcoholic and sexual compulsive with a history of depression, is also the divorced father of a beloved little girl and a man in love; his answer to the question “Would you like to be in a committed relationship?” is, fully and for the first time in his life, “Yes.”

And so his second marriage begins as he emerges, humbly and with tender hopes, from the wreckage of his past, only to be battered by a stormy sea of external troubles—miscarriages, the deaths of friends, and robberies, just for starters. As Moody has put it, "this is a story in which a lot of bad luck is the daily fare of the protagonists, but in which they are also in love.” To Moody’s astonishment, matrimony turns out to be the site of strength in hard times, a vessel infinitely tougher and more durable than any boat these two participants would have traveled by alone. Love buoys the couple, lifting them above their hardships, and the reader is buoyed along with them.

Buy the Book:

Hotels of North America

Hotels of North America (November, 2015, Hardcover)

From the acclaimed Rick Moody, a darkly comic portrait of a man who comes to life in the most unexpected of ways: through his online reviews.

Reginald Edward Morse is one of the top reviewers on RateYourLodging.com, where his many reviews reveal more than just details of hotels around the globe—they tell his life story.

The puzzle of Reginald's life comes together through reviews that comment upon his motivational speaking career, the dissolution of his marriage, the separation from his beloved daughter, and his devotion to an amour known only as “K.” But when Reginald disappears, we are left with the fragments of a life—or at least the life he has carefully constructed—which writer Rick Moody must make sense of.

An inventive blurring of the lines between the real and the fabricated, Hotels of North America demonstrates Moody's mastery ability to push the bounds of the novel.

Literary

Garden State: A Novel (1992)

The first novel written by Rick Moody follows a group of friends in Haledon, New Jersey, through one spring in their rocky passage toward adulthood. They are out of school, trying to start a band, trying to find work — looking for something to do in the degraded terrain of their suburban hometown. Garden State captures the lyricism of stark lives in an intense and unforgettable story of friendship and betrayal.

The Ice Storm (1994)

The year is 1973. As a freak winter storm bears down on an exclusive, affluent suburb in Connecticut, cars skid out of control, men and women swap partners, and their children experiment with sex, drugs, and even suicide. Here two families, the Hoods and the Williamses, com face-to-face with the seething emotions behind the well-clipped lawns of their lives — in a novel widely hailed as a funny, acerbic, and moving hymn to a dazed and confused era of American life.

Purple America (1997)

The story of Hex Radcliffe, a New York City publicist with a stutter, a drinking problem, and a terminally ill mother, who is summoned home to suburban Connecticut and finds himself confronting explosive circumstances and obstacles of comically epic proportions. As the novel unfolds in the course of a single weekend, Purple America lays bare the passions, delusions, and dreams of the American family.

Joyful Noise: The New Testament Revisited (1997)

Twenty-one American writers approach “The Greatest Story Ever Told” with a fresh eye toward its meaning for today. Seeking to reconcile their experiences growing up in the baby boom and Generation X years with their political beliefs and the fractious ethics of the late twentieth century, the writers represented in this collection have looked back to the source text of Christianity. Their essays, which offer interpretations of the New Testament that are eye-opening, passionate, and powerful, will be a source of reassurance and inspiration to anyone who has felt the need to approach spirituality in a personal or unorthodox way.

Demonology (2000)

Moody writes with equal force about the blithe energies of youth (“Boys”) and the rueful onset of middle age (“Hawaiian Night”), about midwestern optimists (“The Double Zero”) and West Coast strategists (“On the Carousel”), about visionary exhilaration (“Forecast from the Retail Desk”) and delusional catharsis (“Surplus Value Books: Catalog Number 13”).

The Black Veil: A Memoir with Digressions (2002)

In this searing, brilliantly acclaimed memoir, Rick Moody reveals how a decade of alcohol, drugs, and other indulgences led him not to the palace of wisdom but to a psychiatric hospital in one of New York’s less exalted boroughs. An inspired portrait of what it means to be young and confused, older and confused, guilty, lost, and finally healed.

The Diviners (2005)

During one month in the autumn of election year 2000, scores of movie-business strivers are focused on one goal: getting a piece of an elusive, but surely huge, television saga, the one that opens with Huns sweeping through Mongolia and closes with a Mormon diviner in the Las Vegas desert; the sure-to-please-everyone multigenerational TV miniseries about diviners, those miracle workers who bring water to perpetually thirsty (and hungry and love-starved) humankind. A cautionary tale about pointless ambition, and a richly detailed look at the interlocking worlds of money, politics, addiction, sex, work, and family in modern America.

Right Livelihoods: Three Novellas (2007)

At the center of “The Omega Force,” the first of three novellas, is a buffoonish former government official in rocky recovery. Dr. “Jamie” Van Deusen is determined to protect his habitat from “dark complected” foreign nationals. His patriotism and wild imagination are mainly fueled by a fall off the wagon. The collection’s second novella concerns a lonely young office manager at an insurance agency, where the office suggestion box is yielding unpleasant messages that escalate to a scary pitch. The book ends with a cataclysmic vision of New York City, after the leveling of 50 square blocks of Manhattan.

The Four Fingers of Death: A Novel (2010)

Excerpt: The Proper Exercise of Power

From the flaps:

“Montese Crandall is a downtrodden writer whose rare collection of baseball cards won’t sustain him, financially or emotionally, through the grave illness of his wife. Luckily, he swindles himself a job churning out a novelization of the 2025 remake of a 1963 horror classic, The Crawling Hand. Crandall tells therein of the United States, in a bid to regain global eminence, launching at last its doomed manned mission to the desolation of Mars. Three space pods with nine Americans on board travel three months, expecting to spend three years as the planet’s first colonists. When a secret mission to retrieve a flesh-eating bacterium for use in bio-warfare in uncovered, mayhem ensues.”

“Only a lonely human arm (missing its middle finger) returns to Earth, crash-landing in the vast Sonoran Desert of Arizona. The arm may hold the secret to reanimation or it may simply be an infectious killing machine. In the ensuing days, it crawls through the heartbroken wasteland of a civilization at its breaking point, economically and culturally — a dystopia of lowlife, emigration from America, and laughable lifestyle alternatives.”

“The Four Fingers of Death is a stunningly inventive, sometimes hilarious, monumental novel. It will delight admirers of comic masterpieces like Slaughterhouse-Five, The Crying of Lot 49, and Catch-22.”

On Celestial Music— And Other Adventures in Listening (2012)

Rick Moody has been writing about music as long as he has been writing, and On Celestial Music provides an ample selection from that effort. His anatomy of the word “cool” reminds us that, in the postwar 40s, it was infused with the feeling of jazz music but is now merely a synonym for neat, “a grunt of assent.” On Celestial Music, which was included in Best American Essays, 2008, begins with a lament for the loss in current music of the vulnerability expressed by Otis Redding’s masterpiece, “Try a Little Tenderness;” moves on to Moody’s infatuation with the ecstatic music of the Velvet Underground; and ends with an appreciation of Arvo Part and Purcell, close as they are to nature, praise, “the music of the spheres.”

Modern groups covered include “Magnetic Fields” (their love songs), “Wilco”(the band’s and Jeff Tweedy’s evolution), “Danielson Famile” (an evangelical rock band), “The Pogues” (Shane McGowan’s problems with addiction), “The Lounge Lizards” (John Lurie’s brilliance), and Meredith Monk, who once recorded a song inspired by Rick Moody’s story “Boys.” Always both incisive and personable, these pieces give us the inspiration to dive as deeply into the music that enhances our lives as Moody has done—and introduces us to wonderful sounds we may not know.

Hotels of North America (2015)

From the acclaimed Rick Moody, a darkly comic portrait of a man who comes to life in the most unexpected of ways: through his online reviews.

Reginald Edward Morse is one of the top reviewers on RateYourLodging.com, where his many reviews reveal more than just details of hotels around the globe—they tell his life story.

The puzzle of Reginald's life comes together through reviews that comment upon his motivational speaking career, the dissolution of his marriage, the separation from his beloved daughter, and his devotion to an amour known only as “K.” But when Reginald disappears, we are left with the fragments of a life—or at least the life he has carefully constructed—which writer Rick Moody must make sense of.

An inventive blurring of the lines between the real and the fabricated, Hotels of North America demonstrates Moody's mastery ability to push the bounds of the novel.

The Long Accomplishment (2019)

Rick Moody, the award-winning author of The Ice Storm, shares the harrowing true story of the first year of his second marriage—an eventful month-by-month account—in The Long Accomplishment: A Memoir of Struggle and Hope in Matrimony

At this story’s start, Moody, a recovering alcoholic and sexual compulsive with a history of depression, is also the divorced father of a beloved little girl and a man in love; his answer to the question “Would you like to be in a committed relationship?” is, fully and for the first time in his life, “Yes.”

And so his second marriage begins as he emerges, humbly and with tender hopes, from the wreckage of his past, only to be battered by a stormy sea of external troubles—miscarriages, the deaths of friends, and robberies, just for starters. As Moody has put it, "this is a story in which a lot of bad luck is the daily fare of the protagonists, but in which they are also in love.” To Moody’s astonishment, matrimony turns out to be the site of strength in hard times, a vessel infinitely tougher and more durable than any boat these two participants would have traveled by alone. Love buoys the couple, lifting them above their hardships, and the reader is buoyed along with them.

Buy the Book:

Rick Moody, Life Coach

Writing constitutes an amazing way to spend your time, it is true, and why, you ask, would I have a dream of becoming a life coach, when I could just continue on in the present way, working on books? I have no response to this question other than the fact that my mother always suggested I should have something to fall back on. I always ignored this advice. However, especially in dark economic times, maybe it’s not such a bad idea. When I was young, I figured — if writing failed — I would be an arbitrageur, or a stockbroker of some kind, and then later, in college, I figured I would be a philosopher, or a psychoanalyst, perhaps a Jungian psychoanalyst. Then I thought maybe a librarian. But lately, I think that I would like to be a life coach.

I am not exactly sure what degree programs one needs to pursue in order to lay claim to the job description of life coach, but I bet the other Rick Moody (the basketball coach, usually associated with the University of Alabama women’s basketball program) has put in more of those classroom hours than I have. He, at least, can do the motivational speaking circuit based on his experiences on the court. My experiences have mainly been at the typewriter or word processor, a place where I am normally very alone. And yet I refuse to allow these things to stop me. Nor will I allow the grim facts of my own life — addiction, mental health problems, childhood in the suburbs — prevent me from realizing my dream. Those who can’t do, teach, it is said. Or else they can run for public office.

And so: while my website is not a site in which there are going to be many direct responses from me to direct queries lodged, there are spots here, and elsewhere online, where those with an urgent need may find someone who can find me, and if there are those of you out there who are in dire need, who require advice, I say bring it on. Bring on your problems. Bring on your lamentable instances of petty envy. Bring on your shoplifting addiction. Bring on your major depression. Bring on your head injury. Bring on your apraxia, or your Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Bring on your alchemical obsession. Bring on your hopes and fears and joys and frustrations. My idea of literature, as I have often said, is that it should save lives. My idea of literature is that it once did save lives, and was of consequence in that way. I believe it can do so again. With every book, to the best of my ability, I try to put this belief in action, even if, as in some of the recent books, the best way to save lives is to cause laughter. Bring on your problems, and I will listen, and bear witness, and when the occasion permits, I will respond, according to certain general rules, on this page, in this hope that here too words may be redemptive.

Dear Hesitant Before the Ambiguities NEW

Hello Life Coach,

I lost my mother Saturday, to liver failure. She had been in poor health for a long time and so her passing wasn’t a surprise, but of course it hurts. We lost my brother (her first-born) eight years ago and she never got over that, and I was grateful that her end was peaceful.

Anyway, it’s my father I’m worried about now, as his whole life has been built around caring for her the last several years, and now he’s alone (with his dog, who is unfortunately in advanced age). They were married fifty-two years. What do you think the lone surviving child should be doing for him (other than the obvious; I’m spending as much time with him as possible)?

Best,

Hesitant Before the Ambiguities

Dear Hesitant Before the Ambiguities,

Rarely has a writerly pseudonym been so evocative! And so rich! I’m trying to figure out on the basis of your note—short and filled with hardship—which ambiguities you are hesitating before. Let’s say, for a moment, that these ambiguities have to do with generational succession, and the way the illness and death of our parents confers ultimate adulthood on us. Whether we want it or not! Is the ambiguity to be found in the fact that you are fathering your father now? And thus, though you were only recently a son, now it seems like it might go the other way? That’s a rich ambiguity, to be sure.

The generational succession issue is also clouded, in your note, by the death of your brother. Having watched the death of a child (my sister) in my own family, having watched the effect of it on my parents, as you have done, I can only concur with the way it just devastates the order of succession. The parents are never supposed to watch a child die, and when they do, and must, the cost unparents them, very nearly, renders them again non-parents, but non-parents who have had a taste of the blessings of children, and now are robbed of these blessings. How do you come back from that ambiguity? That polyvalence of the word “parent.”

Or is there ambiguity, for you, in the simple act of survival when so many members of your family have not? That’s one that I have pondered myself. My mother lost every single member of her family by the time she was 38. Her mom, dad, and brother. And then she lost my sister, her daughter, twenty years after that. Her will to survive all this loss has always been astonishing to me. How to incorporate survival into self, without feeling somehow ashamed? Everything wants to live, of course, or most things want to live, but the human is the animal who has to live with grief, and nowhere for me is the drive to do other than survive, to court the opposite of survival, quite as powerful as when one is grieving. Only time helps here.

But you ask how to take care of your dad, in all this, and then you provide your own very appropriate answer: spend more time with him. So I imagine, Hesitant, that you are not only asking how to take care of your dad (for which you appear to have fine instincts), but also how to take care of yourself. In all of this grief, the easiest thing to do is to find a needy party and make like a machine of anticipation, which machine can find any problem that needs to be solved, vacuum! pick up prescription! write thank-you notes!, without ever slowing down long enough to ask: what is it that I need now, for myself, so that I too can go on and grow into the fullness of MY adulthood?

Is the hesitation of your pseudonym a recognition of the difficulty of this particular moment of self-care, a hesitation before the responsibilities thereof? Let me put it more plainly, Hesitant. Are you going to take care of yourself too? Is there someone who loves you to whom you can come home after the visits with your dad, into whose lap you can put your head and weep over all of this? At least as long as the weeping is still useful? Because maybe that is important under these circumstances. This Life Coach is too geographically distant come to your house, Hesitant, and provide his own lap, but this Life Coach hopes that these words might be like a literary fainting couch, where you could put down the immensity of your burdens, and allow the dermal layers of loss to shuffle themselves off in language.

Middle age, and one’s own death, these are the things that are bounded on the one end by the demise of one’s parents. Gazing at the dramatic extremities of this situation would cause anyone to be hesitant. But my argument is about not forgetting the great responsibility of middle age, taking care of ourselves! Recognizing when we have gone beyond what the body is able to accomplish. Or, put it this way, if we are to parent ourselves now the way our parents are perhaps no longer able to do, the thing we should remind ourselves of at the close of each day is this: “You have done enough today, and now you should rest. There will be plenty of time tomorrow to solve all of the world’s problems, and to make sure that all of your nearest and dearest can get through another day.”

All admiration for your selflessness in this sad time,

Rick Moody, Life Coach

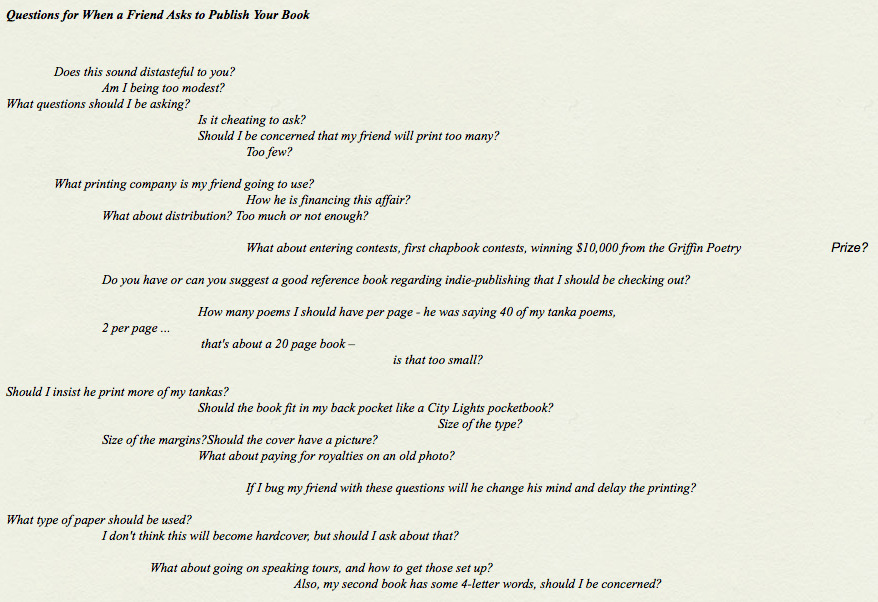

Dear Ian Caton NEW

Dear Ian Caton,

You ask so many questions that your letter reads, in a way, like Whitman himself, and so I have taken the liberty of setting your letter as though it were a poem. It is herewith.

Ian Caton, these are all reasonable questions, really, and they are the perfectly reasonable questions of someone who is publishing his first book. Later on, when circumstances grind you to a pulp, you will ask fewer of these questions, because you will be more concerned with feeding your children, or surviving for another 24 hours. (This is not necessarily a good thing, but it is my experience.) Moreover, it will be abundantly clear (alas!) that some of these questions are beyond your control. My advice is to choose battles wisely in the publishing process, and to decide which issues are essential for your emotional well-being (font, let’s say, or front cover), and then allow for negotiations on everything else. As a general rule, unless you are Stephen King even a front cover is somewhat beyond your control, though you can influence this to some degree if you are graphically-minded and well informed about design.

Publishing a book is a collaborative enterprise, as such, you the author cannot have everything you want. So you should want fewer things, in order to achieve maximum satisfaction with the process. Interestingly, your insistence that your publisher is “your friend” strikes me as the biggest potential problem on the horizon with respect to your publication. Not the paper stock, nor the front cover image. I have found over the years that there is a natural tendency to become friendly with one’s editors and publishers, because you are working with them for a spell, sometimes for a long spell, and therefore you get to know one another, and it all seems quite friendly. But at the same time many of these editors and publishers work at the pleasure of their supervisors and they are meant to be making money for the corporation (this does not apply as rigidly with small presses, but neither are the small presses immune from the profit motive), and when there’s a hitch in capitalist part of the project your friendship is liable to feel secondary to business pressures. Your life coach has occasionally found this to be exquisitely painful, the friendship so quickly sacrificed for the sake of business. What a horrendous sentence is the sentence that goes: “Nothing personal! It’s just business!” One smiles through the grief.

The most important thing for a writer to do is work. What is unimportant are the facts of publication. Only marketing people should ultimately care about that stuff, and that’s their job, and it’s good that they do their jobs with such verve. But I advise finishing up manuscript number two, and then manuscript number three, Ian Caton, and let no man (and no front cover image) deflect you from that solemn task.

Best wishes,

Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear Anonymous NEW

To Rick Moody Life Coach, From Anonymous,

I have an almost constantly racing mind—racing without any choice of subject at all. Often there is a rushing-in review of absolutely anything from the past, from any point in time, followed by an unrelated thought chain… It can be as mundane as a conversation with people in line at a bank, from twenty years ago! We discussed how to know who goes first at a stop sign when all arrive at once! And if it is at the 12 o'clock—where is 12 o'clock?????

I am ONLY 50, so I don't think this is an end-of-life kind of re-examining. I have indulged some selfish and decadent behaviors—and suspect that guilt makes my mind crowd out, rather than focus on, troubling episodes also… Another thing—I read books back-to-back(of course some of them have been, and will continue to be, your books) and can't NOT be reading a book, or I feel very lost…Possibly feeling like I've stopped learning…

Is it a mixture of these things? Are they related?

Thank you for your writer's wisdom,

Anonymous

Dear Anonymous,

I, Rick Moody, Life Coach, have a lot of identification with your note. With the symptoms you describe. While I am not a medical professional, I feel relatively certain that there are medical professionals who would pathologize your symptoms, based on your description, and give you something something speedy to alleviate your discomfort. But as we have all had enough of these sorts of solutions, I would like to explore other options here. First, I would like to explore the possibility that your need to be reading books back-to-back is not only non-pathological but wholly admirable, even slightly heroic. While I am loath to feel heroic myself, I often feel the same way about books. My wife would attest to the fact that I have feelings of nervous anxiety when I am out in the world without a book. In fact, if I am on the subway, or, worse, on a plane without a book, I am a very unhappy person. Sometime I will tell you the long story about how I was on my way home from Scotland, once, after an attempted terrorist bombing in the UK, and was told that books would not be allowed in my hand luggage. It was one of the most uncomfortable days of my life. My symptoms were close to withdrawal symptoms. I think, Anonymous, that your love of books makes you, in fact, better than most of your peers, and you should feel entitled to take some pride in this. Which is to say: the portion of your letter about books is a slightly heroic portion, for which, from this life coach, you will get only gratitude and admiration.

As regards the other symptoms—the swamp waters of the past, the racing mind—I see these as being, in part, the sign of the half-century mark. It is true, in terms of raw computing, that when you are in the middle of your life's journey, as I am too, more memory space seems to be given over to the past than to the present, and that the short-term events often fail to have pride of place in the cranial storage facility. Apparently, remembering conversations from middle school is far more important than, e.g., that student's name from my class last fall. It is upsetting to me regularly, this last-in-first-out storage protocol, but I also often find that if I slow down, court a bit of serenity, and avoid beating up on myself, all the cognition I need is there for me. At the same time, and I think almost any middle-aged person would submit, the cognitive valleys of this AARP time of life are matched by ever more wise and insightful human abilities. I know more about how humans feel now, and I care more about humans, than at any time in my life. The mildest poignancies around me, of a kind that I would scarcely have credited in my twenties, now seem almost operatic in their pathos. And I think this is a good thing. It means that I am attending to the present, even if I can't always remember the names and faces (I am so bad with faces!). You indicated this kind of wisdom, yourself, with your reflection about decadent behavior when younger. I feel your regret there, and that regret is the site where growth can take place.

The past is past. Look back, but don't gaze. And as for the present, and its hurly-burly of sensations, my advice is not to pathologize these feelings you are having, but rather accept them as the nature of circumstances. Be where you are! Because there are so few alternatives. You are not your younger self, but you are no less than your younger self.

And: I feel certain that when you and I meet, if we do, that we will have a lot to commiserate about.

Sincerely,

Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear "Mom" NEW

Dear Rick Moody,

My daughter is a published writer (short story journals). She has an MFA from Cornell. She is 37. She teaches at a writers workshop for barely nothing. She also does tutoring. Three years ago she received an email from a well-respected agent saying he was interested in her work and could she send him her 50 pages? She has yet to do this she has 49 pages. We have had a series of unfortunate events happen in our lives. Her marriage ended violently soon after the birth of her only child, her husband went into a mental institution shortly before the breakup for five weeks - he was in the Navy, an EOD officer. The Navy had to step in and help her leave before he was released from the behavioral institution. She had a military protection order in place and they moved her to her childhood home. She then proceeded to get full custody of the child and a restraining order. He has only visited the child once, under my supervision. He has been separated from the Navy and has stopped paying child support. So we are on our own. She is hanging in there and is a terrific writer. She needs some sort of encouragement to continue on and I guess it is not enough coming from her mother. She grew up in a different world than this going to private school and horseback riding lessons. Any advice?

PS. She worked as a journalist for a magazine and interviewed many celebrities. She is extremely bright and a lovely person inside and out. She has lived in Rome and taught ESL there.

Dear "Mom," you didn't attach a name to your note, and thus, for today, and especially because of your maternal thoughtfulness, I'm calling you "Mom."

What you describe above, with your daughter, is a mountain of extremely good material, as far as I am concerned. Novels are made from adversity. Or, perhaps, human wisdom is made from adversity, and novels are made from human wisdom. The net effect is the same: lots of material. That said, there are the two kinds of writers in the world, those who produce the work and those who do not. The horrors of domestic turmoil have lain waste to many a writer, and there is no guarantee that one can manufacture in oneself the wherewithal to get clear enough of the turmoil to convert it into language. You, "Mom," cannot make her do it, nor can I make her do it. She has to want to do it.

I think for some writers there is no decision about this; the writing just happens. Turmoil is automatically converted to vowels and consonants. For myself, I find, as the poet Yeats said, I write to know what I think. I have no grasp on my own difficulties (they are legion) without finding a way to write about them. And thus whatever your daughter is going through she may feel now that it is too overwhelming, too time-consuming, to be written about now. But I say that writing about life is the only way to feel better about it! So why not?

Her credentials, as far as I can tell, are good, and she has the toughness to work hard at teaching, etc. Obviously, there is no guarantee that the agent will take her work if she writes the one additional page, but if she never writes the one page, she will never know. Finishing is part of being a writer, letting the work out into the sunshine of public opinion. Not easy, to be sure, but it beats the alternative. I urge her to do it, you are urging her to do it, and maybe there is real good that can be done by her converting all this hardship into literature. Maybe she can help other people. But she has to want it.

Writers can convert their luck at any time, if they really want to.

Best wishes,

Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear Dinty NEW

Dear Mr. Moody,

Why do people, and by people I mean co-workers and students, erupt every once in a while with absolute crazy? How should I react?

Dinty

Dear Dinty,

I believe we are both laborers in the academic world of writing instruction. I will confine my experiences to this world, about which, like you, I do know a thing or two. This I say simply so that other readers of the Rick Moody, Life Coach, column can appreciate where you and I are coming from.

The semester is just over here in my neck of the woods. In fact, I write you just days after the end of the semester. And this semester definitely had its moments of the wobbly sanity. I could go on at some length, but I do not want the mentally ill or post-traumatic to feel unduly judged by me. I love all my students even when they are unsteady. I always feel their aches and pains.

Your questions are, 1) why? and 2) what to do about it?

The obvious answer to question #1, why why why?, is simply that a generous portion of writers suffer with symptoms of mental illness. I remember seeing a study when I was in writing school that argued that the profession with the highest portion of mental illness of all (and this may perhaps have included soldiering and lighthouse operation) was in fact the profession of “poet.” Somehow I felt slightly disappointed for being a prose writer, perhaps because I erroneously associated mental illness (I was 24 years old at the time) with heightened creativity. At any rate, it may be that the romance of writing (and its tendency toward madness), and the dark truths to be found there on occasion, attract some unstable personalities, encouraging them, in academic settings, to act poorly. And it may be that the academic life tends to be stressful and to drive people toward ends of the semesters in ways that are counterproductive to good mental hygiene. The workshop itself, moreover, is a highly stressful setting, in which supportive and helpful criticism is sometimes set aside and replaced with vituperations or highly competitive maneuvering between writers.

This would perhaps account for why the students are often crazy. But what about our colleagues? Why are they so capricious and enraged and bitter? This is a question I have asked of myself, over the years, many times. Why must academic politics, departmental politics, be so fractious and sociopathic? My working assumption has always been that the piece of pie is so small (one tiny endowed chair, one tenure track job), and the people competing for it are so ill-equipped to do anything else, that they imagine they have no recourse but to fight to the death. That would be a reasonable explanation of the phenomenon in part. Except for this: the bigger, better-funded departments, engineering or law, are just as riven with dispute. If you consider that academic life has its origins in monastic study, you would think we could all do better. The monks didn't need to hound one another to death. This secular monasticism, this monasticism with an excess of holier-than-thou should be so much better than it is, but maybe when you strip the God out of the guilds of study what you get is all the bad and none of the good. (Not that Christian education is much better! Maybe Christian education is more like secular education than ever before!) Perhaps I simply cannot answer this particular WHY, but I can, in my capacity as life coach, affirm your observations. Your observations are entirely accurate.

So, 2) what to do about it? I think you already know the answer here, Dinty, because I believe you have been at it even longer than I (and I am closing on my 25th year of teaching). The answer is to do as little as possible about the madness. This semester I had a bit of a stalking situation, a stalking-lite situation, which I had done nothing to encourage, but it embarrassed me to a great degree. I tried to do nothing for as long as possible, to stick to a bland and non-engaged kindness, such as I would offer any student, or anyone who expressed interest in my class. When this was no longer practicable, I did in fact solicit the department chair, to tell the student in question that I just wished to teach my class without incident and then to go home. Because that in fact is all I want to do. I love the actual subject matter of my classes—writing and literature—and I feel honored to teach anyone about them. Everything that is not about the dissemination of the actual material, between myself and student, is noise to me. I don't care about committees, I don't care about the institutions of higher learning, I don't care about my university, I don't care who's better or who's more attractive among the students, or anything else. At all. I care about the ideas, and the passing them on. So what I do, and I'm sure you do it, too, is tune out, or calve off, anything that is not the actual material of my class. I make myself as unavailable as possible for all the rest of it. In class, you get 100% of my attention, and out of class, you get as close to 0% of my attention as I can get while still maintaining control of my teaching project. This preserves the organism so that he can teach again another day, and also so that he may, on occasion, write.

Make sense?

Have a good summer vacation,

Rick Moody, Life Coach.

Dear Existential Dread

Dear Rick Moody, Life Coach,

I’m writing this letter because I feel very trapped. I’m writing this letter to you because you are the only person of my literary influences alive today. (The others who I would have considered writing this to, who I have written this letter to only in my head, would be Mike Gordon — more musical than literary — Sartre, Vonnegut, or David Foster Wallace. And, as I actually sit down to write this letter, I think to myself that you are probably the most level-headed out of the bunch so perhaps this is working out better than I expected.)

I’ve been told that I’m a good writer. People seem to like what I put out. I won a few poetry slams too. But I am never chomping at the bit to write for long periods of time. I chomp at the bit to come up with stories and I do that almost endlessly. I love creating the puzzle. I love making things work seamlessly. But then it comes to actually write the stories. When it comes down to it, I enjoy outlining the story and imagining the story more than I actually enjoy writing the story.

I was diagnosed with ADD when I was very young but I never realized the impact that it actually had on my life until recently when I made the decision that I was going to give writing a real shot.

I’m a graduating senior and I write this during my last winter break ever. I dedicated this winter break to pursuing writing at a more serious level than I had before. I found that I’m trying to balance on a double edged sword. If I take my medication, I can get work done but it lacks any real zest. I lose my creativity when I take my medication. Even when I take it, I can’t work for that long. If I don’t take my medication, I will be flooded by invention and creativity but there’s a catch: when the wind blows, I must find a new activity. I will actually get up and go do something else without having ever realized that I was doing something beforehand.

This does not fare well for writing stories. It worked when I wrote poetry because I could write it one line at a time but I’m bored with poetry. I much prefer reading and writing fiction.

I am told that I am a writer. I dearly wish I was but I don’t think I have the focus to do so. I feel very trapped. I have a drive to create stories and worlds but I have no drive to put those stories into writing. I don’t know what to do with myself. I feel as though I am becoming something, some person, and it defies my very efforts to shape it. I feel uncomfortable because I have every opportunity the world can offer and I feel that I am squandering my resources.

I think, and this is what makes me think that I am not a writer, that if I was a writer, I would want to write more. I’m not sure what direction to push my life towards. I’m at a crossroads but all the street signs are blank. I want to keep heading straight, on the road that includes writing, but the effort to keep my wheels straight makes me think that it's “not meant to be.”

Summed up, I suppose my issue is such: I thoroughly enjoy writing but I cannot commit myself to it as much as I try to do so, as much as I want to do so. I’m graduating in May as a Philosophy and Creative Writing double major without any real skills. I feel incredibly anxious that if I cannot be a writer, I don’t know what I can be. I have to like what I’m doing otherwise I’ll just be bored, frustrated, and resentful as I walk away. The only thing that really absorbs me is coming up with stories. Writing stories, past the outline, turns into a chore. All I want to do is put down what I’m working on and go to the next project.

Do you, in your new post as life coach, have any advice on what I should do?

Sincerely —

Existential Dread

Dear Existential Dread,

I’m writing this on the plane between Atlanta and Jackson, MS, not a place where I am all that often, nor a region where I feel terribly comfortable. But it’s what I have on my plate this week, and accordingly I have a fair amount of dread myself. So I should identify a little bit, and I do, at least with the part where you are wanting to write and having trouble finding the time and concentration in which to do it. Writing is always, these days, at this moment in history, in danger of being crowded out by seductions of the instantaneous. That, in far, is the great lie of digital culture, that things can always be more instantaneous. I was on a panel at South by Southwest recently, and I had to listen to a lot of this bunk about how the kids just want to be able to listen to the music now, and are not willing to tolerate having to wait, and don’t want to pay, because they think all the music is free, and that is the future. I just don’t believe this at all. I don’t believe the kids behave in a monolith, and I don’t believe that they are all against paying for things that they believe in, and I don’t believe they all believe that everything has to be instantaneous. I know in my own case, Existential Dread, that everything I have worked for and suffered for has been better than everything that I have got for free. Free is cheap, and cheap is usually the you-get-what-you-pay-for category.

But what happens if we want to make art but we just don’t feel like we have the constitution for making art? There are any number of questions I would ask in reply to this one, but perhaps the most important of these would be: what makes you think there is only the one way of making art? There are many ways to skin that cat, and some people manage to find ways to work within their limitations with great success. William S. Burroughs would be one example. Ginsberg had to assemble Naked Lunch for Burroughs because Burroughs just wasn’t up to coming up with a structure. Burroughs improvised the “routines” at the heart of the book, and then just dropped the leaves of paper in his apartment in the Interzone, and then it was left to Ginsberg to assemble a meaning of the whole. Of such things are careers made. A more recent example would be Mary Robison’s excellent novel Why Did I Ever, which takes the ADD life as a leaping off point for itself. The action, such as it is, and there isn’t much, is carved up into tiny bite-sized morsels, one-liners. Not much plot, not much character, occasional moments of drama, but more frequently just bits of comedy and weirdness. And totally great! Robison supplants the expectations of conventional fiction with these little filaments of language, and they are incredibly catching. You get taught how to read this book, as you go, and the edification goes down easily, with much delight.

One of the first things to do, perhaps, is to stop thinking of the symptoms of ADD as pathology, at least insofar as they apply to creative work. Your instrument is different from my instrument, but that’s all. (I have recently been reading Jonah Lehrer’s Imagine, and it has some interesting things to say about focus, about how people with focus are sometimes less creative and imaginative, because imagination, in part, depends on strange leaps and associations, associations that have little do with focus) So it’s not a pathology. In the end, it may be hard, because you have been taught for years that you should think differently from how you natively think. But maybe it’s possible to start thinking about this ADD business as an asset. That is exactly what I suggest you do.

Assuming following through on stories is a chore, how to make a story out of mere “outlines?” That part is easy, as far as I’m concerned. Try making a really big catalogue of outlines. What if you made a story that’s just called “Twenty-Five Outlines for Abandoned Stories?” A simple catalogue of all the stories you’ve never finished. Or what if you called it: “From the Library of Uncompleted Projects,” or what if you called it: “Need A Story? See Below,” and then people could write to you and request stories, and you would just give them one of the stories you have yet to finish? There are many ways to bend the structure of fiction, which is only linear and predictable now and then, so that it serves your particular way of being.

You have probably graduated now, or are about to graduate, because this has taken so long. And I apologize on that front. I have been teaching quite a bit lately. But I will say, now that you are a graduate, and likely a little anxious about what comes next, that all you have to do to be a writer is write, and if you really want to do it, you can do it. Just start where you are, and proceed along the journey in that direction.

Best wishes, Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear Arthur

Dear Rick Moody, Life Coach,

First off — I’m stoked that you have this ‘life coach’ impulse. The idea that literature has a life-saving imperative is something I’ve always unquestionably believed from the moment I read Kerouac in my all-boys Catholic school and had my gourd rocked wholesale and it is downright invigorating to know that others share this faith.

The reason I am writing is because I am in dire need of a life coach — I have something resembling a set of half-baked questions which with due pluck I might be able to articulate, but more than anything what I'm missing is a soothing voice of wisdom whose counsel amounts to an understanding of what the meaningful things really are and how to fight for them.

I can ramble at length but in the interest of directness over too much ponderous word-wombatting some context might be helpful: I grew up in a small beach town in Queens once known for boozy Irish barfights, now increasingly under siege by Ray Ban clad Brooklyn hipsters with bad haircuts. My parents immigrated from Poland to bring me to streets of gold in America, only for my dad to find work paving the streets himself until he joined the electrical union and moved on to hanging temporary lights.

As mentioned, I went through twelve grades of Catholic schooling — wracking me with inexplicable guilt about all too many things and a strong affinity for Good Will Hunting hoodrat types. At some point in high school I found Kerouac and went from being a long time reader to a first time writer, waxing beatific with all the woeful teenage angst that is so glorious to lampoon but oh so profoundly important at the time. I found Brown through a track meet, and was sucked into the admissions spiel of a place where we could all be architects of our own educations. I originally had my eyes set on writing, without really understanding what it was, how to do it, or what learning to write at a place like Brown would look like. I floated through the humanities for the next four years, graduating with a degree in Africana — critical theory meets social philosophy, with a sprig of postcolonial race politics for flavor — ostensibly keen on understanding the shaping of worldviews as a net goal.

As it turns out, I graduated this past May dimmed from within on all too many degrees of academic sophistication, whatever embers of curiosity had me seeking an open education in the first place long since extinguished by the new SAT robot hustle. I went home and went back to work in the stained glass studio I grew up apprenticing in as a kid, until lo and behold I got a phonecall from a hedge fund in CT and am now forehead-to-desk deep in ‘work’ with a lease on a two bedroom in suburbia to boot.

In short, while I have a broad brush narrative of how I have gotten here and am by and large content with life as it is, I can’t help but hear the creaks of my bookshelves whimpering out that there’s something more to life that I might have dropped sight of along the way. At any given point in my soggy Marxist days in Providence I would have been on the other side of the Occupy fence, but out of a distaste for doing things for their moral veneer and the practical realities of a furloughed father and a vague sense that it’s better to be doing this vs. barbacking or barista’ing I find myself in the peculiar predicament of waking up a lap into a race I didn’t even know I was running.

I’ve read your Dear Anita and Dear Concerned Writer letters as well as your bit in the Atlantic which have been profoundly uplifting and directional, but my question/s are a little more spectral: What is it that drove you to writing? What are the experiences in life that have been most meaningful to you? How have you grappled with your sense of direction as your path meandered? What mentors, fictional or otherwise, have remained with you over time? Take these questions for what they are — vague attempts at articulating my sense of listlessness, feel free to answer whatever question it is I should be asking.

For what it’s worth, I apologize if this letter comes across as too literary — I have a horrible knack for putting on airs when writing about things that matter to me even to friends and family, meaning I’m self-concious about being self-concious and I wind up a postmodern turkey stuffed with confusion from the outside in. I’m not sure if you’re still teaching in the NY area or not, but if you have office hours or coffee time it would be totally boss if you had any time to chat as a mentor / life coach (if it cuts down on the need to reply).

Thanks, truly —

Arthur

Dear Arthur,

As I told others, recently, I have been a little out of touch with the Life Coach part of my life, partly because I was being a dad so much of the time, but I am back, at least for a little while. And I am moved by your letter, and by the decision to use “wombatting” as a word, and especially by using the double consonant in “wombatting,” which, back when I did a little editing, was considered “New Yorker house style,” c.f., “travelling.” I think the Chicago Manual might prefer a single t with “wombatting.” Let it be said: I liked the style of your letter, and I like the predicament: hedge fund guy with heart of gold. It’s not all that often I am called upon to give people advice on making too much money.

Here’s your relevant passage, as I understand it: “What is it that drove you to writing? What are the experiences in life that have been most meaningful to you? How have you grappled with your sense of direction as your path meandered? What mentors, fictional or otherwise, have remained with you over time?”

These are all big questions, Arthur. Part of what’s hovering underneath your uncertainty, in my view, is a particular legacy of your Catholic education: you want to be called to a profession. This is a way of thinking about vocation that is unique to people saddled with a Christian education, but that doesn’t mean that it’s so horrible. In fact, wanting profession to have romantic, ecstatic qualities is noble. Especially when, as you are, you are coming from a family when work was just work. You want to be called, and I admire it.

Maybe some socialist training at Brown helps with the idea of a “calling” as well. Because, after all, nothing is so Christian — in terms of its dogmatism, and its ideals, its valorization of the disenfranchised — as orthodox Marxism. I know it well. I was there when “politically correct,” as a locution, was born. We always used quotation marks when employing it in those days, but how quickly were the quotation marks removed.

In your wish to be called, you ask me, as I interpret it, if I was called to writing myself. And I suppose I would answer yes, if I could define the term my own way. For example, as to your first question — “What drove you to writing?” — I think I would have to say that I have no idea. I only know that I was driven. That is, some of the impulse was automatic. And a calling in this regard is that impulse that has no known causative agent (otherwise known as, in religious circles, God). I read a lot, and that was preliminary to writing, but in the end the writing happened because it happened, and assuredly not because anyone thought it was a wise vocational choice. Even I didn’t think so.

Your second question goes further afield: “What are the experiences in life that have been most meaningful to you?” I assume you are asking about this in order to try to assess whether I need meaningful literary experiences in order to want to write. But my list of meaningful experience is pretty far-ranging. My parents’ divorce was meaningful for me (in 1970), my learning to play soccer was meaningful for me, reading Moby Dick in high school, learning to play piano was meaningful, my bad LSD experience in 1978 was meaningful for me, my love for Elizabeth P. Breckinridge was meaningful for me, my first encounter with Samuel Beckett in 1979 was meaningful for me, first playing the electric guitar was meaningful for me, first hearing Music For Airports was meaningful, taking Semiotics 12 at Brown was meaningful to me, my sister’s death in 1995, my time in the psychiatric hospital in 1987, living in Hoboken in the mid-eighties, and so on. There have been many such things, not all of them about writing at all. Sometimes a great many different experiences can make of a person a writer, but mostly meaningful experiences just are, and should probably be treated as such.

Next, you ask about meandering: “How have you grappled with your sense of direction as your path meandered?” And the answer to this is easy. I love meandering! I will go wherever it goes! That is fine with me! I think it will all go somewhere interesting! So there is no grappling involved. Life is meandering. The idea that it has an orderly shape is an effect of the 19th century English novel. I think the aimlessness of life is very real, and part of the pulse of things as we experience them. “Digressions are the sunshine,” Sterne says, or something like that. So there’s no grappling here, only acceptance of the facts.

“What mentors, fictional or otherwise, have remained with you over time?” All of them, of course. I could do some kind of hierarchical ranking, but I don’t think that is in the spirit of your inquiry. Maybe the larger question here is: do I still feel that my mentors are relevant, and do I still feel that being teachable is relevant, and to this I can answer with a resounding affirmative. I have been thinking about the Buddhist concept of beginner’s mind, recently, trying to get myself back to the place in my own creative world where I don’t know everything, and I am willing to see things without the relentless armature of experience that I unfortunately bring to a lot of my work. With this in mind, there are mentors at hand, almost all the time, and being willing to accept them, being willing to accept what they offer, is part of growing and changing and adapting to what is creative about life. I am not perfect at it. But I try.

So, Arthur, you parents came here so that you could do better than they did, and you did, and you are, and you are making money, which is part of how people evaluate “doing better,” for good and for ill, and you had a fine enough education that you are now wondering if you might not do something else, something that calls to you. You think that maybe literature is calling to you. I can’t answer that part for you. And I can’t tell you how to weigh the burden that you must feel for having parents sacrifice for you in the particular way that they have. But I can say that there is no point in life, ever, where the route is foretold. There are always the accidents, the bomb bursts of the unexpected, the eruptions of history, the side journeys, and the dawning awareness that one might have done otherwise. If this isn’t the life you wanted, you can remake it at any time. And sometimes books are the thing that can best dramatize this road not taken. I know well how they can call.

Best wishes, Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear Elizabeth

Dear Rick Moody, Life Coach,

I am not sure this is the email address to be sending an unabashed fan letter, but it is the only way I found to contact you on your website. I am writing you because I am a writer pretty much in total awe of you. I am also feeling lost with my own work, so sending this message to your Life Coach e-mail address is fitting, I guess.

Last year, I saw you read at George Mason with Jennifer Egan. I’m in the MFA program there. Your reading was excellent. I was a bit stunned in fact. We met for a second after the reading but I was feeling very shy that night. I even stupidly turned down dinner with my professor and Jennifer Egan.

Now I have just finished The Ice Storm — this morning, sitting up in bed. From page one I was obsessed by your structure — the tight two days unfolding the lives of the Hoods and the Williamses, the point of view shifts, all told by Paul. The Ice Storm is simply one of the most brilliant books I have ever read. Thank you for it.

I have also read interviews with you and articles and I know that for a long time you struggled with getting published. I’ve never been published, either, though not for lack of trying. I write fiction. I am working on a novel. I am struggling a lot with the structure — and because I am just sort of writing random scenes and notes and things about my characters, I can’t tell if I’m bullshitting. And thus my fear is that I am not a real writer, and certainly not a novelist. But then, maybe I am just in the beginning stages. And I guess, how will I ever know if I am a real writer? What’s a real writer? Does it mean being published? If I keep writing, I hope that makes me a writer. But does it?

Anyway, those are my Life Coach questions I guess. I want to thank you again for The Ice Storm. I have just ordered The Four Fingers of Death. I’m really looking forward to delving into all of your work, and trying to understand what makes you such an incredible writer.

Best, Elizabeth.

Dear Elizabeth,

The Rick Moody, Life Coach, franchise has been mothballed for a while, because I was trying to work on some other things, and teaching a lot, but suddenly there is a backlog of letters. I feel honor-bound to try to respond a little bit, lest you all feel that you are voices in the wilderness. And so here I am.

I am grateful for your kind remarks, which open your missive, but the substance of my reply will be paragraph four, i.e., your questions about the Years of Struggle, as I have often called them. The first important point is: there is no such thing as a real writer. What would the anatomical requirements be for a real writer? Is one a real writer only when has published for real. But of what would such publication consist? And if one had published for real, but then, e.g., fell silent, would one no longer be real writer? What if one only wrote letters, as Richardson is reputed to have done before he wrote Pamela. Would he not be a real writer, for having composed only his correspondence, before someone persuaded to try to make a novel out of the letters? And if he foreswore the novels (after three of them) and retreated to letters, would he no longer be a writer? Is a writer of unpublished writing not a writer? On what basis would real be relevant? Is real not merely a term bandied about by parents of young people when they are worried about the ability of these young writers to make a living? And if that’s the case, if it’s just a word for your parents, are you not duty bound to reject it? Why do we want to be real writers, anyway, when being an unreal writer might somehow be more heroic, and more kin with what it means to care about fiction as a form? In these times of alleged reality hunger, would it not be more noble, and more lofty, to be an unreal writer? It is, as the saying goes, a self-diagnosed illness, this thing of ours, and only you get to say when you are it. I would offer only one caveat, Eliz., and that is: writers are the ones who actually put words down on a page. If you are not writing anything down on a page, then it would be hard to lay claim to the term writer. The amount of writing is not germane. Nor is the instant value. Put some words down, think them over, and then make the self-diagnosis, if it applies.

As for novel writing: it’s just really very hard. There’s a reason why every other book, in my own case, is either stories or some other form. Because novel writing requires immense amounts of commitment. The more you commit, the better is the result. Think in terms of giving most of your writing time away for three years. That’s a reasonable presumption. At the end of three years, see what you have. And in the meantime, be extremely patient. The novel is the journey of a thousand miles that begins with a step. The first step has a lot of vertigo associated with it, but that’s okay. If you are patient and have courage, at the end of the long commitment that is novel writing, you will have something. And, at least from my point of view, anyone who writes a novel is the genuine thing, a writer of the unreal.

Best wishes, Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear Residual Matter

Dear Rick Moody, Life Coach,

I’m not sure I know where to begin, let alone if I’ve ever begun or seen things beginning, and knowing where to begin always seems so displaced and incoherent anyway, like when I begin a conversation with someone and it all depends on that very moment from the get-go, whether or not she supports me in my research, he reproaches me for having asked for a recommendation, they reject me from whatever program or grant or conference.

So I’m sure I don’t know where to begin, but I’m asking you for advice because your writing always gets me, somehow similar to the way a friend gets me, or a lover gets me in bed, or even a bedfellow in the morning, when we wake up and joke about not knowing how we ended up next to each other in this particular situation, but I guess I’ve always thought of words as friends in most cases too, or at least, always as bedfellows, falling asleep with books most nights when I don’t have anything to worry me up until the crack of dawn.

More or less, I’m asking you where do I go from here. It’s a vague vernacular, how we ask for the going and never the coming, when the bottom line is contingency. But I’m in this sticky hole I’ve dug for an education, which has advanced me inasmuch as I can say I’m a comparativist and creative writer now, though most of my old professors would say, “Really?” and probably laugh after I’d left. The problem is I’ve more or less taken out a home mortgage to graduate with a BA, when in fact I live in a hole-in-the-wall apartment in Brooklyn with sky high rent. And I didn’t really want to live in this specific apartment, it’s just that the apartment I initially paid a broker’s fee for, well, the management company for that apartment screwed me over by not telling me I had bed bugs until three days before I had to vacate the premises of my old apartment in Crown Heights. So what do I do? I look at some twenty apartments in a day and pick the one that will let me move in the day before my roommates and I are evicted.

Anyway, I graduated, but in fact that’s not helped me become gainfully employed. Back on the student debt fund. And now I’m in an MA program, where I don’t feel comfortable with my knowledge of the idiom in which the professors speak, let alone with my attendance to social events and presenting myself, becoming a stereotype among competitive graduate students who aggressively attack each other’s egos while pissing in the bathroom, seeming to be a masterful candidate for a degree that also won’t help me do much of anything but teach foreign language classes in a language I still don’t fluently speak. I’ve always been a reader anyway, and a slow reader at that. The fact of the matter is that I’ve disappointed my advisor, I don’t have a third recommendation for my PhD. applications, and I’m thinking, well, maybe I should go to school for an MFA. But I doubt I have a third recommendation for those applications also.

Where do I go from here? It’s not like I’m totally alone in this boat either. My boyfriend’s sinking in debts, while he interns for a film distribution company. His parents, luckily, are paying back his student loans. Mine wouldn’t even if I fled to another country. And then there’s the matter of the dog, whose smile gets me in the sense of getting that immediately came to mind when I wrote that sentence three paragraphs back about your writing. I’ve been thinking about going to Hoboken but I hear the prices are just as high as in Brooklyn. I imagine this wasn’t the case when you wrote Garden State, lowest rent being somewhere around $800 to $1000 a month for a studio, though who knows?

My advisor is an especially critical thinker, whose criticism of my writing three weeks ago nearly devastated me to the point of concluding all my aspirations for becoming both a writer and a professor. My ex told me I’m just on the next level and I shouldn’t give up, but I don’t know if that’s the case, although I’m not sure there’s anything I can do as a back-up plan to teaching besides manual labor. Then there’s the other professor who said I reproached him, recriminalized him last year when I wrote him about my rejection from a department. But he’s not pleasant in any sense of the word: I’m sure he’s bound up in extremely sadistic ties to pedagogy. Yet, what he said still had me stuck in his office at a loss for words whose absence led to a tense feeling in my eyes and my own absence from his office. Tomorrow I have to present a talk at a conference, and my paper’s not even conclusive yet, though who can conclude when interpreting desire? Coextensive with this question, is what’s my desire in writing to you? What’s my demand?

Perhaps I wrote you in friendship, uncertain about whether I could even take part in a friendship with anyone whose writing I admire. After so much anxiety and worry over meeting my present advisor and speaking with her, I’m not sure I can admire my friends. I’ve started to return to what Jacques Derrida says about pity: how it’s the strongest drive in life with the exception of self-love. I imagine I’ve successfully failed at persuading you to let me learn from you, though I am a student at NYU. I’m on the internet thinking you’re teaching a class next semester there, maybe I can enroll in your course, if I could just find your e-mail. Then I find this place where I can ask for your advice as a life coach. I think twice about writing an e-mail just to inquire if I could at least audit your course, when I come to terms with the fact that I probably need a therapist of some sort but I’ve always been extremely resistant to therapists and psychoanalysts, I don’t trust their work, as much as I invest heavily in most of Freud’s writing as a critical thinker. Same goes for Lacan, if not more so in regard to his work. I’m still very much at odds with his law of the psychic life that every letter arrives at its design or destination. There’s a chance; there’s always a chance it won’t arrive, especially on time.

On that note, I think I should just send my e-mail and wait for your response. I see myself failing and falling, while there’s also the recent drinking problem I need to overcome. I broke my boyfriend’s guitar one night probably because we both had too much, and then I spent too much money on a ’68 semi-hollow Silvertone to compensate for my bad behavior, but I still feel like a real loser. To add to that, I still haven’t gone back to the dentist a second time to fix the front tooth I chipped while trying to keep a beer from overflowing this past summer. I have recurrent dreams about my teeth falling out now, though I never had them before I chipped this front tooth. It’s not so much unmanageable to have a tooth fixed or to stop drinking as it’s difficult to schedule my life in any ordinate way. Part of me wants to move far away, like to Antarctica — if only Werner Herzog hadn’t already romanticized doing that.

Looking forward to your response, Some Residual Matter to the Specter of Derrida.

Dear Residual Matter,

Part of what interests me in your note is the way in which you are repudiating both the origins of things—in paragraph one: “I’m not sure I know where to begin, let alone if I’ve ever begun or seen things beginning, and knowing where to begin always seems so displaced and incoherent anyway, like when I begin a conversation with someone and it all depends on that very moment from the get-go”—and likewise the idea of concluding—in graph six: “My advisor is an especially critical thinker, whose criticism of my writing three weeks ago nearly devastated me to the point of concluding all my aspirations …” Which would certainly seem to imply that you are a person much taken up with the middles, and this is supported as well by your use of the glorious word contingency, in graph three: “It’s a vague vernacular, how we ask for the going and never the coming, when the bottom line is contingency.”

Let me, in this regard, quote from Richard Rorty’s excellent book Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity that seems to have much to do with your situation, wherein he is describing the modern ironist: “(1) She has radical and continuing doubts about the final vocabulary she currently uses, because she has been impressed by other vocabularies, vocabularies taken as final by people or books she has encountered; (2) she realizes that argument phrased in her present vocabulary can neither underwrite nor dissolve these doubts; (3) insofar as she philosophizes about her situation, she does not think that her vocabulary is closer to reality than others, that it is in touch with a power not herself.” The feminine pronoun is in the original! Sounds like your letter a little, bit, huh?

Yes, there is relativism abroad in the land, and that is a good thing, and, yes, there is no location more likely to try to grind out of you all the relativism and all the irony than the modern academic department. Why it is that an endeavor that is largely based on the love of study, and text, and art, is so much given over to a kind of ritual child abuse that persists generation after generation, regardless of who is ambitious to work in the field and who is being spit out of it? I don’t know the answer. I only know that my own encounters with departmental politics in writing programs, etc., does not convince me that an MFA, as a degree program, will be substantially better than a PhD program.

Your predicament reminds me a little bit of a Chekhov story. Chekhov, in the reductive literary critical retrospect, is the author of the “slice of life” story structure, in which both beginnings and endings are missing. Why are they missing the beginnings and endings? Because “reality” happens in the middle, and is where things are less sentimental, less formulaic, less overdramatized. The middles are where things are more uncertain, more contingent, more human-scaled. And if there is a time of life that is most Chekhovian, most given to implication, and also to uncertainty about what comes next, it is youth.

Add to this, the sense that youth has these kinds of things as part of it—bedbugs, poverty, annoying academic advisors—the notion that America, post-great-recession, is a petri dish for desperation and uncertainty, and you wind up with the idea, Residual Matter, that you are probably right where you are most likely to be at the moment. In the years when no one knows what the fuck is going on. You have my complete sympathy. I lived through my twenties, but they were hard, and I suffered a fair amount.

That said, it is my passionately held belief, that no one who is drinking abusively has ever helped their circumstances dramatically by doing so. I can tell you, as this is a well-known feature of my own story, that I was not a good writer during my own period of problem drinking. So it is worth thinking about whether problem drinking, and the brownouts and blackouts, and the slaughtered guitars, and the suffering relationships that go with problem drinking are not adding to your burdens. There is plenty that can be done about problem drinking, as I’m sure you know.

Meanwhile, I know I’m slow here, as I took some time off from life coaching, but you’re welcome to sit in on my class, if you like. You have to talk though. No one is allowed to sit in without contributing.

Best wishes, Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear Shit Gone South

Dear Rick Moody, Life Coach,

I just can’t seem to get my shit together since everything went south. What’s next?

Sincerely, Richard.

Dear Richard,

Before I get to answering specific questions such as yours, I want readers of this page to know that I recently composed not one but two short stories by gluing together answers to questions I solicited from friends. Advice stories! In that case, the respondent, the answerer, was an small-town advice columnist guy, who, in the course of responding actually went belly up. He deceased, that is, though this did not stop the flow of advice. At some point, these wholly fictional stories will turn up in a book, I suspect, a book possibly entitled Stories With Advice. I don’t want you (or any of the others who are reading this deep into the web site) to imagine that those stories, when they finally appear, are somehow influenced by this experience, the experience of Rick Moody, Life Coach. On the contrary, my regular life is always influenced by my fiction, not vice versa. My advice, here, in this specific locale, is shot through with my experience as a writer of fiction, and not much else. I am not really good at anything else, but the fiction writing. So my advice is confined thereto. It orbits around my experience as reader and writer.

That said, let me address your specific question. You are using fecal imagery to describe your life, Richard, and leaving the aside the issue that I too occasionally use fecal imagery to describe my own life, I wonder why this locution is so popular. What is it about “shit” that should be “together?” Why do we find this so compelling as a way of thinking about life? Why shouldn’t life, or our “shit,” be more apart, less coherent? I personally kind of like the unruly and predictable course of events when I am not controlling these events, and I find, in those moments, that the sense of not having to make orderly what is naturally disorderly is much more to my taste. So the first thing I would advise, if I were any good at advising, would be that you stop thinking of your life’s work as “shit,” and second that you stop attempting to assemble this “shit.” Which then brings me to everything “going south.” Again, I have used “going south” as a synonym for abject failure often in my own life, and I suppose that I have because I have mixed feelings about travelling into the often conservative regions of the Deep South. Would you still say your “shit” had “gone south” if you lived in New Zealand? Then you’d be talking about the South Island, which is actually a really beautiful place, and nothing like, let’s say, Tuscaloosa. I think we should try to recast the South in a way that is not so glum, as regards the colloquial usages thereof. If you purge the “shit,” the shit needing to be “together,” and the idea that “going South” is somehow to be avoided, then where are we with your question? Then you might be asking: Dear Rick Moody, Life Coach, life is unpredictable, what to do? To which I would answer: avoid prediction!

Best wishes, Rick Moody, Life Coach

Dear Dying Alone

Dear Rick Moody, Life Coach,

I have a gnawing suspicion that I will be dying alone. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that everyone I know ends up leaving me. Perhaps it is because I live alone with seven cats. Perhaps I am helplessly neurotic. Perhaps it is because I live like a hermit and cry a lot. Nonetheless, this is my gnawing suspicion. What say ye, Rick Moody, Life Coach? Do you think I will be dying alone? Is this a question you can answer? Or have I mistaken you for psychic Sylvia Browne?

Sincerely, Possibly Dying Alone With Many Cats

Dear Possibly,